Ruffling feathers: a luxury for the few

Earlier this month the Supreme Court upheld the validity of the criminal defamation law.

‘Hurt sentiments’ are in the news again, this time with All India Bakchod (AIB) member Tanmay Bhat's video of a mock conversation between Lata Mangeshkar and Sachin Tendulkar provoking howls of protest.

The BJP in Maharashtra and Raj Thackeray’s MNS have filed police complaints against Bhat. Mumbai police say, according to reports, that they will contact Google and YouTube to block the video. Bhat’s attackers are outraged at this defamation of two legendary Indians and the case highlights yet again the many permutations that defamation and criminal defamation can take in India.

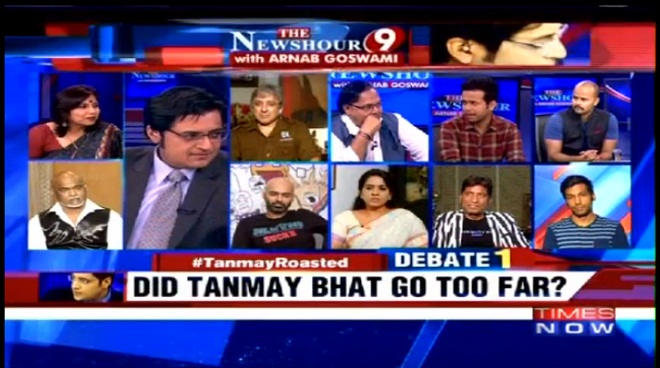

It can be a comedian like Bhat making fun of famous figures; a powerful person trying to silence a critical journalist; journalists making scurrilous attacks against powerful people with no evidence; the media using fake stings to tarnish a private individual; a TV anchor making serious allegations against an individual such as Arnab Goswami recently accusing a journalist of being a terrorist; and finally it can be communities citing their ‘hurt sentiments’ over an ostensible slight to their beliefs by a person, film, show, or painting.

Criminal defamation has been much debated in recent weeks after the Supreme Court laid it out in the honourable judge’s purple prose for the 21st century India. The court upheld the Constitutional validity of Sections 499 and 500 of the law dealing with criminal defamation and section 119 of the Code of Criminal Procedure while dealing with a batch of cases filed by Rahul Gandhi, Arvind Kejriwal and Subramanian Swamy.

Many senior journalists were justifiably interested in the outcome. The judgment was declared a disappointment for it upheld the provisions, raising fears that such a legal weapon in the hands of public figures who ought to be accountable will have a chilling effect on investigative journalism.

There can be many different scenarios in defamation litigation. In one scenario, a corporate entity or a powerful politician may haul an investigative journalist to court on ‘criminal defamation’ charges. Such cases indeed can have a chilling effect, as the journalists chosen for such treatment tend to be high profile and can be used as a warning for smaller fry. In fact, much of the debate around the judgment was by senior journalists from this vantage.

The argument resonated particularly loudly in the context of the Strategic Lawsuit against Public Participation (SLAPP) suits sent by the Ambani brothers to Paranjoy Guha Thakurta and others for writing and distributing Gas Wars, a book that substantiates and corroborates every piece of information presented in it with documentary proof.

Attacking public figures because of political motives

Not all journalism is done in the public spirit, with the same accuracy and veracity as Gas Wars.

Exactly 30 years ago, the iconic Illustrated Weekly of India ran two stories and some box items in its May and August issues against J.B. Patnaik, the then Congress chief minister of Orissa. The cover stories were titled, “Shocking! The strange escapades of J.B. Patnaik, Orissa’s chief minister” and “He is a pervert.”

Patnaik filed a libel suit for one crore which drew to a close three years later in an out-of-court settlement and after an abject apology by Bennett, Coleman and Company. It read, “We, Bennett, Coleman and Company Ltd, Pritish Nandy, editor of the Illustrated Weekly and S.N.M. Abdi, special correspondent of the Illustrated Weekly, had published two articles under the captions 'The strange escapades of J.B. Patnaik' and 'Why is J.B. Patnaik being allowed to gag the press' in the issues dated 18-24 May 1986 and 3-9 August 1986 respectively, based on information available to us."

“Subsequently, we found that the information, on the basis of which these articles were written, was not true and was politically motivated. We regret the damage done to Mr Patnaik's reputation and offer our apologies to him."

S. Nihal Singh wrote at the time, “Seldom has an apology by a major Indian publication been as demeaning, particularly in acknowledging a political motivation in writing the original report. Every journalist felt diminished by the nature of the apology”. Bennett, Coleman & Company closed the 70 year-old Weekly after a couple of years.

Using fake videos and unsubstantiated allegations to tarnish reputations

That was a time when commercial news television did not exist in India. Today we have instances where fake videos are used for framing sedition charges as in the case of the JNU students, Kanhaiya Kumar, Umar Khaled and Anirban Bhattacharya. The students’ photos were shown in the media. They were labelled anti-national. Cases were filed based on the dubious video evidence.

The relentless coverage given to the issue on news channels made them targets of death threats and physical assaults, in addition to their arrest and incarceration for several days. Members of their families were also under threat. Not only were their reputation's seriously damaged, but their right to life was threatened.

The power that media houses wield is likely to be far greater than that of any ordinary citizen. When New Delhi government teacher Uma Khurana’s reputation was hurt in 2008 due to a fake sting operation showing her involvement in a prostitution racket, she was trashed on Live India TV under the able editorship of Sudhir Chaudhury (of ZEE TV now). The channel was punished by being pulled off the air for a month, but what redress, if any, Khurana received in the out-of-court settlement is unknown.

In a more recent example, the Times Now anchor Arnab Goswami alleged on air that Asad Ashraf, the Tehelka journalist, was a cover for the Indian Mujahideen because Asad's investigation exposed the loop holes in the police version of the Bathla House encounter.

In today’s climate, such branding of a Muslim can seriously endanger their life and liberty. It is deeply defamatory for a journalist to be accused of being a terrorist sympathiser. Are the channel and the anchor not accountable to prove the basis for their accusation?

In the same piece on the BCCL apology referred to earlier, Nihal Singh also wrote, “It is legitimate for a publication to try to enlarge the limits of freedom. But it must take the rap if it obviously offends against good taste. Above all, it must have a fool-proof dossier before launching a major attack on a leading politician, or a humbler soul.”

The kind of aversion to defamation litigation that we see today apparently did not exist then, though journalists then were unanimous in their opposition to the infamous Defamation Bill that sought to curtail freedom of speech that the Rajiv Gandhi government attempted to bring in. They succeeded in getting it shelved, but there was no serious debate about the existing provisions of the defamation law and their impact on free speech.

Flexing corporate muscles to deter criticism

The perceptions of threat may have changed since then because by the mid-1980s, Bennett Coleman & Company adopted an aggressive policy of filing defamation cases against any slightest hint of disrespect to itself, just as the Ambani empire does not allow anyone to ruffle its feathers. This lowering of the tolerance threshold among corporations may have increased the threat perception.

On the contrary, none of the individual victims have taken the news channels to court on charges of criminal defamation with malicious intent. In cases such as those of the JNU students and the Tehelka journalist, the channels once again appear to have acted with political intent and did not hesitate not just to defame but to seriously imperil the lives of the victims and their kin. This speaks volumes about power structures and the impunity with which the news media can operate entirely powered by their corporate muscle.

Hurt sentiments get traction but not adivasi rape victims

Meanwhile, there is an extensive and intensive ‘hurt sentiment’ brigade all over the country which operates on the fringes of the defamation law, but uses different provisions with a better strike rate. While in defamation cases the test of truth, mala fide intent, public interest and the right to reputation of an individual etc., are all considered, when it comes to ‘hurt sentiments’, the mere generic claim of disrespect to a community or person appears to be sufficient to lodge a case.

So this brigade can file FIRs in local police stations and get people arrested and put away. We have seen this happen in the case of the two young girls, Shaheen Dhada and Renu, who were arrested for a Facebook post, on the grounds of promoting enmity/ill will between classes, for objecting to the bandh on the day of Bal Thackeray’s funeral.

Another case that is brewing in Hyderabad is that of Prof Kancha Ilaiah who said at a Centre of Indian Trade Unions meeting on 14 May that “The Brahmins as a community have not contributed anything to the production process of the Indian nation. Even now their role in the basic human survival based productive activity is not there. On the contrary, they constructed a spiritual theory that repeatedly tells people that production is pollution.”

Brahmin groups, allegedly with the encouragement of I.V. Krishna Rao, IAS, Chairman of the Andhra Pradesh Brahmin Welfare Corporation (yes, such a thing does exist in the new state of Andhra Pradesh!), threatened Ilaiah at his office and then went on to file a case against him.

Exactly one year back in May 2015, the Vishwa Hindu Parishad filed a case against Ilaiah claiming hurt sentiments over his article in a local newspaper, Andhrajyothi, titled ‘Devudu Prajaswamya Vaadi Kaada’ (“Is God not a democrat?”). Ilaiah had to get a stay on criminal proceedings for writing that article.

And now the Offence Brigade has descended on Tanmay Bhat. The Central Board for Film Certification Chief, Pahlaj Nihalani, called for Bhat’s arrest under the Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act and recommended that he be denied bail. Nihlani declared, helpfully, that Bhat is a ‘repeat offender’.

Such cases are filed with alacrity and police action is swift in this country where otherwise dalits, minorities, adivasis and women cannot get an FIR registered over atrocities or gang rapes. In Bastar, even after the adivasi women deposed about gang rapes before a committee headed by Justice Suresh, the police said that they have to do a preliminary enquiry before they can register an FIR, defying National Human Rights Commission and Supreme Court guidelines.

And the less said the better about those who are involved in cultural politics like Sachin Mali or Deepak Dengle of Kabir Kala Manch who write and sing political songs for creating awareness of rights. Such people are arrested under draconian laws like the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act or MCOCA and put away for a long time, without trial or bail.

In many instances of legitimate grievances, the police stations refuse to file FIRs. Recent examples show that hit and run cases involving celebrities, public lynchings, and the virulent abuse of women, are ignored. The Information and Broadcasting Minister, Arun Jaitley, recently advised us to get used to abusive trolls. But a spoof on celebrities is of course blasphemy. The police are already hunting for Bhat’s IP address (or so it has been reported) and consulting legal experts.

Celebrity feathers are holy, while the whole bird can be killed and consumed if it happens to be powerless. In all the instances, the common thread is the equation of power between the attackers and the victims. Those who are on the side of the state, or have access to its networks of influence, can always defy the laws and use the laws to harass the powerless.

The police and the political class are there to protect brahminical hegemony, the business class, and the bureaucracy. The rights guaranteed under the Constitution of India that say all are equal before the law have been undermined and reduced to a rhetorical mythology that sounds attractive in Independence day and Republic Day speeches. We need to finally recognise the truth that has been staring at us. It is not which laws exist and how they are worded that matters. It is who has the power to implement them or not.

Padmaja Shaw is a media scholar, columnist, broadcast journalism trainer, and a retired professor of journalism.