A riveting chronicle

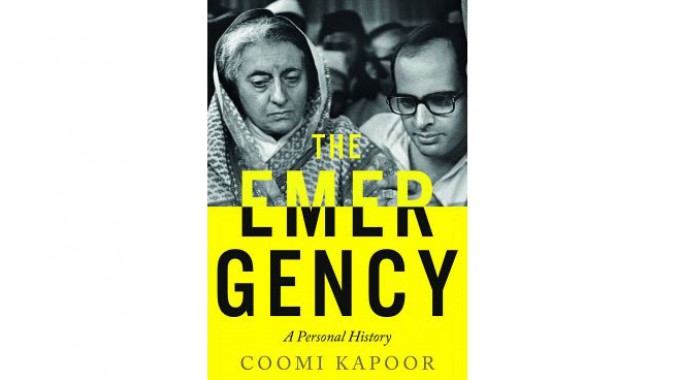

The Emergency: A Personal History, By Coomi Kapoor. Penguin Viking, pages 389, Rs 599.

Many of us can remember that sweltering day of June 25, 1975, when the electricity kept going off. Power outages were not infrequent but as a reporter covering the municipality, Coomi Kapoor was asked by her news editor at the Indian Express to ensure that the power supply would be restored by late evening for the presses to print the morning’s paper. Kapoor did the needful, little realizing that a far greater breakdown would occur next day.

Forty years on, there is such a plethora of written and recorded material on the Emergency that it seems difficult to reconstruct a fresh chronicle of the nineteen nightmarish months that shook the nation and transfixed the world’s gaze on India’s seemingly inexorable slide into dictatorship.

Yet much of this material is also dated, scattered and virtually erased from history - for instance, copies of the Shah Commission’s voluminous investigation into the Emergency’s excesses. Indira Gandhi withdrew and destroyed copies from libraries and government institutions after she returned to power in 1980.

Coomi Kapoor’s account of that tumultuous period is, therefore, the most comprehensive, detailed and rivetingly arranged, especially for a younger audience unacquainted with Indira Gandhi and her younger son Sanjay Gandhi’s ruthless authoritarian regime that derailed democracy.

Marshalling a vast resource of newspaper and photographic archives, memoirs, biographies, government records, private letters and diaries, and personal interviews, she brings alive a narrative that is in the best tradition of journalistic reportage. It is also lived personal history by someone who was put to hardship and distress by the unleashed reign of terror.

Like one of the rare copies of the Shah Commission report, which she obtained from the parliamentarian Era Sezhiyan who had copied and edited the original for his personal record, her book has other scoops of the kind that have marked her long career as a reporter of distinction. Chief among these is a personal handwritten letter by Siddhartha Shankar Ray, the suave barrister and West Bengal chief minister, written to his old friend Indira (he was one of the few people to address her thus) dated as early as January 8, 1975, in which he spells out a secret plan to promulgate a special ordinance and order mass arrests throughout the country.

“The idea is to swing into action immediately after the ordinance is ready - and it has to be ready in 24 hours’ time from now. I hope the President will be available to sign the ordinance. Also a special Cabinet meeting should be called etc…”

It is through such documents that Kapoor shows that the Emergency was not a sudden crackdown and not a knee-jerk reaction by Mrs Gandhi to the Allahabad High Court judgement of June 12 that found her guilty of electoral malpractice and barred her from holding any elected post for six years. In fact, the storm clouds had been gathering all the previous year in a series of corruption scandals, strikes and the Bihar students’ agitation led by Jayaprakash Narayan that induced in her vacillating, suspicious mind a paranoia that she would be unseated, and that her wheeling-dealing son Sanjay’s future, with his doomed Maruti car project and arrogant, controlling cronies, would be placed at serious risk.

Events then moved with terrifying speed, acquiring a momentum that seemed even outside her control. Opposition and student leaders (among the latter Arun Jaitley who was jailed for the entire 19 months), activists, journalists and aristocrats such as Gayatri Devi of Jaipur and Vijayeraje Scindia of Gwalior, were rounded up and imprisoned.

The ambit of the dreaded Maintenance of Internal Security Act (MISA) was expanded, alongside other provisions, so that no credible reason had to be given for the arrests. At the Emergency’s peak, Kapoor estimates that over 150,000 people filled the jails, a far greater number than during the 1942 Quit India movement. She gives a list of 18 high court judges “transferred for delivering judgments not to the government’s liking”.

There is other detailing too in this book which brings alive the orchestrating of both harassment and propaganda: the number of prosecutions launched against the Indian Express’s Ramnath Goenka—320—with no magistrate giving an exemption from personal appearance, the 3000 page charge sheet filed against George Fernandes with 575 witnesses listed, the number of lines AIR would give in a single month to the spokesperson of the Congress party (2207) as against those to the opposition (34 lines).

Civil rights and human rights were suspended and a five-member Supreme Court bench upheld the government’s appeal in the mounting pile of habeas corpus petitions. The media was tyrannized into submission with widespread censorship and daily monitoring of news. At one place she lists the topics on which censorship orders were issued, and at another cites a series quotes from the kind of fulsome coverage Sanjay received from AIR.

Ministers were summarily sacked or shunted out, including Information & Broadcasting Minister I.K. Gujral who as rudely upbraided by Sanjay: “You don’t seem to know how to control your ministry. Can’t you tell them even how to put out the news?” Mohammed Yunus, a Gandhi family loyalist, demanded BBC correspondent Mark Tully’s head more crudely: “Pull down his pants and give him a few lashes and put him in jail.”

The ordeal became personally harrowing for Kapoor. Her husband and fellow journalist Virendra Kapoor was picked up and thrown into Tihar Jail after a minor altercation at a public meeting with Ambika Soni, then a leading light of Sanjay Gandhi’s Youth Congress.

“It is indicative of the terror prevailing at the time,” she writes, “that no Indians, not even colleagues, were prepared to give evidence on the circumstances surrounding Virendra’s arrest.” Although briefly released on bail, he was soon rearrested under MISA, a routine practice at the time.

Life as a prisoner’s wife, with a small child and meagre resources, was hard enough but became more difficult when he was suddenly transferred to Bareilly jail, after an outlaw called Daku Sundar and his gang made their escape from Tihar. Travelling in overcrowded trains with a sick baby to visit her husband, she describes the appalling conditions in the provincial jail.

The story of her brother-in-law, Harvard economist and politician Subramaniam Swamy and at that time a Rajya Sabha Jana Sangh MP, was more dramatic. To evade arrest (some 25,000 RSS workers were arrested after the organization was banned) he disguised himself as a Sikh and travelled widely in the country and overseas to rally support against the Emergency.

“In Gujarat, the RSS often sent a young pracharak to pick him up from that station…this humble pracharak was Narendra Modi, who would become leader of the BJP and prime minister four decades later.”

After more than a year on the run, Swamy, returned incognito from America and made a sensational appearance in parliament before once again managing a Houdini escape. With their husbands absent, Coomi and her sister Roxna bore the brunt of reprisals as prime suspects: their homes were ransacked and their staff and relatives, including their parents in Mumbai, constantly harassed. Police sleuths continually tailed them: “I travelled by bus and the police followed in a motorcycle and car.”

With a detachment borne of distance in time, and in clear dispassionate prose, Kapoor’s accounts are not sequential; rather she picks themes to draw a vivid portrait of a period that the American playwright Lillian Hellman, in a similar era of oppression and persecution during the McCarthy witch hunts, called “scoundrel time”.

Other than chapters devoted to the complex mother-son relationship, Sanjay’s weird coterie of cohorts that included school buddies, car mechanics, handpicked civil servants, police officers and socialities, and the horrors of his forced sterilization and urban beautification programmes that led to untold misery, violence and deaths, Kapoor also includes masterly profiles of her employer, media baron Ram Nath Goenka, and the firebrand trade unionist George Fernandes.

Wisely, she does not go into turgid analysis and speculative “what if?” scenarios to ask if a repeat of the Emergency is possible. Deftly piecing together an intricate jigsaw that is backed by evidence and many facets of events and personalities, she leaves it to up to the reader to judge.

If there is a singular impression that Coomi Kapoor’s compelling history of the Emergency leaves, however, it is in the best-known definition of the concentration of authority: “Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.’

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.