Bold new plans by North East rebels

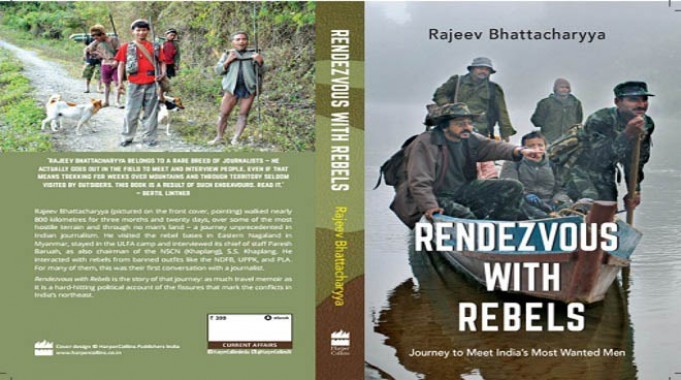

“Rendezvous with Rebels”, Rajeev Bhattacharyya, HarperCollins India, 2014, ISBN 9351363171, 9789351363170, 328 pages, Rs 399

Attention is riveted once again on the beleaguered North East following one of the biggest attacks on the Indian Army in Manipur by the newly-floated common platform, the United Liberation Front of Western South East Asia (UNLFW) comprising NSCN (K), ULFA (I), the Kamatapur Liberation Organization, NDFB (Songbijit) and some other Manipur-based groups.

Journalists and intelligence agencies are on overdrive to gather information about the operation, about the groups that carried it out and the factors that help their sustenance in Myanmar. One man who saw it all coming was Rajeev Bhattacharyya as his new book, Rendezvous With Rebels: Journey to Meet India’s Most Wanted Men demonstrates.

Bhattacharyya’s detailed account of the events in the build up to the formation of the United Front and the government-in-exile will provide readers with the perfect prologue to the present violence in the North East.

It will also help readers understand the reasons for, and the background of, the failed peace process between the Centre and the NSCN(K). The North East insurgency and the neighbouring countries of India are intricately related and the book makes no qualms about these facts.

Rendezvous With Rebels is an elaborate account of the region where some of the traits associated with modern human civilisation are not yet discernible and where government and counter-government forces and laws are in perpetual conflict.

Journalism in the form of sitting comfortably in air conditioned newsrooms took a backseat when Bhattacharyya and his colleague crossed into Myanmar illegally and trekked the upper, mountainous region of the Sagaing Division of the country to the joint headquarters of some of the most prominent rebel groups.

The book can be read in two completely different ways. From one angle, it is unmistakably a travelogue through some of the remotest terrains of the South-east Asian region that few from the mainstream world have ever visited. The descriptions of the terrain and the unique experiences of interacting with ancient Naga tribes and customs make it quite an interesting read, as are the author’s observations on the advent and spread of Christianity in a region dominated by a headhunters till only a few decades ago.

Though Bhattacharyya’s writing sounds anthropological in some parts, it does not feel like a digression, rather it fits nicely with his larger narrative. The eight pages of photographs that he took himself during the trek also capture some rare moments.

From another angle, the book is an account of the North East insurgency from the ground and contradicts the multiple clichéd narratives that exist. Bhattacharyya knocks down many myths by generating fresh information through his interactions with rebel leaders, so much so that his book can serve as a handbook on the Naga insurgency.

The Assamese version of the book was named Paresh Baruar Sandhanot which means In Search of Paresh Baruah. Though the English version hasn’t mentioned the elusive Commander in Chief of the ULFA in the title, there is no doubt that Baruah is the focal point of the book.

Other rebel leaders such as Khaplang have interacted with journalists before but this was Baruah’s maiden face-to-face interview and hence the excitement it generated is understandable. In fact, the only shortcoming, if any, of the book is that this interview failed miserably to live up to the immense expectations. Baruah shied away from answering most of the questions and whatever he answered was mostly the daily stuff that he sends out to the media in emails and telephonic conversations.

The most crucial point was perhaps the factional breakup of the ULFA with the Arabinda Rajkhowa-led faction coming forward to talk with the government and settle for a peaceful solution. But very little is discussed about this and Baruah instead speaks about Assamese chauvinism and the typical mindset of the Assamese intellectual middle class that, according to him, has led to the identity crisis and statehood demands in Assam.

This statement comes as an important stand in the wake of the various separate statehood demands within the state of Assam. But the ULFA’s long term position on demography and the geography of the idealized state that the organization is fighting for remained unanswered in the interview.

As happens in most of these cases, the pre-directed guidelines laid down by the rebel leaders for interviews restrict the raw version of what they said from reaching us. This creates gaps in the narrative flow which better editing would have sorted out to a great extent. If the Paresh Baruah interview failed, it nonetheless provided an invaluable insight into his psyche. In any case, it’s not every day that one gets to hear the views of a wanted, elusive rebel leader like Baruah from close quarters.

The interview with Baba, alias S.S. Khaplang, chairman NSCN(K), proved to be the surprise package which the author admits he wasn’t even aware of till the very last.

Startling information regarding the unofficial pact of peace between NSCN(K) and the Myanmarese junta has been revealed. Bhattacharyya notes that two months after their return, NSCN(K) concluded a written agreement with the Myanmarese army that formalized the ceasefire between the two sides. This pact of peace with the official army of a neighboring country and the recent ending of a ceasefire with the Indian government by the rebel group is of utmost significance and speaks volumes about the state of geopolitics in the South-East Asian region.

After such an exciting narrative, the book ends abruptly and the reader is left wanting to know more about Bhattacharyya’s return journey. If you want an insightful and fresh account of the insurgents of the North East, along with fascinating glimpses into the daily life and customs of Naga hamlets that still remain completely isolated from the modern world, buy this book.

Such articles are only possible because of your support. Help the Hoot. The Hoot is an independent initiative of the Media Foundation and requires funds for independent media monitoring. Please support us. Every rupee helps.