How the Pew report on Modi was covered

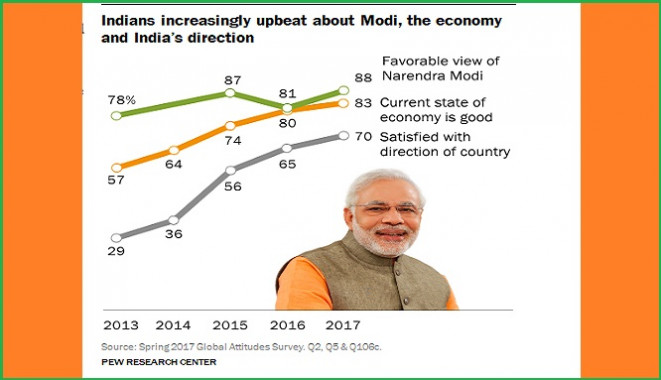

The report of the Spring 2017 Global Attitudes Survey of the Pew Research Centre has evoked enormous interest in India. Pew is a non-partisan fact tank based in the United States (most of our media has referred to Pew as a think tank.) The results of the survey were extensively reported in the media and can help us understand how politically salient numbers are used in our public debates.

Most of the coverage was framed by the title of the Pew report: “Three Years In, Modi Remains Very Popular” (emphasis added). This is reflected in the coverage starting with the headlines. Rare exceptions aside, the headlines reported the key findings of Pew, completely ignoring the fact that they held good for the period between February 21 and March 10, 2017.

A few examples are in order: “‘Narendra Modi remains by far the most popular national figure in Indian politics,’ finds Pew study” (Scroll); “9 out of 10 Indians approve of Narendra Modi, says Pew survey” (LiveMint; “Despite note ban, GST, Modi wave still prevails: Survey” (The Tribune); “Modi remains popular” (HT; “PM Narendra Modi 'By Far' Most Popular Figure In Indian Politics: Pew Survey” (NDTV); and “Despite note ban, Narendra Modi remains overwhelmingly popular: Pew research” (The Indian Express) (emphases added).

Perhaps only one headline was careful in so far as it clearly indicated that the survey data are of historical value: “Modi Remained Popular Even After His Cash Ban, Poll Says” (Bloomberg Quint, emphasis added).

Two other headlines stand out: “Indians are still hopelessly in love with Narendra Modi, says a new Pew Report” (Quartz India) and “Sheen intact, but Modi falling short in fight against communalism, pollution: Pew poll” (Times of India).

Otherwise, most headlines misjudged the contemporary relevance of the report and ended up presenting an overly positive image of the ruling party.

The timing of the survey received some attention in the coverage. A DNA report alerted readers in this regard: “The survey was held in February-March this year, before the implementation of GST and before Indians got to know that 99% of notes again went back to the system post demonetization. So one has to interpret 83% of people happy with economic situation of India in that context” ("From South India’s love for PM Modi to his Pakistan problem: 5 things Pew Survey tells us beyond the obvious").

Financial Express (“Pew survey a shot in the arm for Narendra Modi; 10 reasons why Rahul Gandhi should be worried”) and a Firstpost article (“Pew survey results boost Narendra Modi's popularity, but Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh polls remain litmus tests”) also noted this point.

Bloomberg Quint alone carried Pew’s clarification regarding the validity of the survey results in light of the subsequent downturn in the economy. While Pew noted that its survey cannot capture how public sentiment might have changed in response to later economic problems, it also pointed out that for the relevant period “satisfaction with the economy was widely shared across demographic groups.”

Some newspapers were, however, too eager to claim that the survey proved that people were happy with the management of the economy despite demonetisation and the introduction of GST.

Contrary to the headline of The Tribune, the Pew survey did not ask any question about GST, which was introduced months later. India TV too claimed that while the Opposition’s "claims" that the economy has been severely hit by Centre’s reforms like demonetisation and GST,” the survey suggests that “around 80 per cent Indians are contented with the situation of the nation’s economy.”

Firstpost did not claim that the survey results imply that Modi’s popularity remains unaffected by GST, but argued that the government has adopted corrective measures with alacrity.

BusinessLine was, on the other hand, not clear in this regard as it notes that GST-related problems would have affected the BJP and then adds that the survey found the contrary: “A poorly implemented goods-and-services tax that went into effect in July has further unsettled small businesses, many of which are part of the bedrock of the BJP's political base.

“But the poll found that more than 80 per cent of those surveyed said economic conditions were good, up 19 percentage points since just before the 2014 election” (“Modi remains overwhelmingly popular, says Pew poll”) (emphasis added).

Only one news item went beyond simplistic analysis of the impact of GST on public sentiment and voting preferences and highlighted other intervening socio-political considerations: “People might think demonetization and GST were executed poorly, but there are other factors - from caste to local candidates - that make people vote for the BJP,” said Sanjay Kumar, a director at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, or CSDS (“Modi Remained Popular Even After His Cash Ban, Poll Says,” Bloomberg Quint).

Not many newspapers paid attention to the geographical spread of the sample. The Pew survey was “conducted in the Union Territory of Delhi and in 16 of the 18 most populous states, Kerala and Assam excluded.” These states and Delhi account for about 90 per cent of the country’s population.

DNA alone paused to ask if the results would have been different [at least for South India] had Kerala been included (“From demanding tougher action in Kashmir to BJP supporters trusting media: 10 things Pew survey said about India”).

A brief news item in The Hindu explained why Pew excluded Kerala, but unlike DNA it did not ask if this influenced the results (“PM’s popularity high: Pew study”). The Hindu also highlighted an important point not noted elsewhere: “While the survey concluded that Indians seek a hardline approach to the Kashmir issue, it did not include the State itself in the survey.”

Except in a few cases, the coverage lacked both empirical and analytical depth. IndiaSpend briefly pointed out that the Pew results compare with surveys conducted by CSDS: “In May 2017, 44% Indians said they would prefer Modi as prime minister, in a survey of 11,373 individuals at 584 locations in 146 parliamentary constituencies spread across 19 states by New Delhi-based political research organisation CSDS. None of Modi’s competitors polled in double digits in the CSDS survey” (“No Match For Modi Yet As Many More Indians Say Country On Right Track: Pew Survey”).

This was, however, not followed up by further comparative discussion as most of the space in the article was filled with twitter screen shots.

Likewise, two pieces published in DNA were perhaps the only ones that make a serious attempt to explain/understand the facts thrown up by Pew in their totality by trying to situate the findings within larger developments: (From South India’s love for PM Modi to his Pakistan problem: 5 things Pew Survey tells us beyond the obvious and From demanding tougher action in Kashmir to BJP supporters trusting media: 10 things Pew survey said about India).

A final observation is in order about the newspapers/websites that published more than one article. The two DNA articles referred to above differ in a crucial respect. The latter of the two does not refer to GST, which has possibly affected Modi’s post-demonetisation standing.

Firstpost published three pieces. Of these, two commented on Pew’s methodology. One of them questioned the validity of the survey as its “sample size is too small,” while the other endorsed Pew’s methodology.

A valid question that was not asked except in DNA relates to how the findings vary with religion and caste, the two key determinants of electoral outcomes. It is here that Pew survey’s limitations become evident as the sample size is not large enough to allow calculation of reliable estimates for smaller sub-groups of population. Also, the design of the survey questionnaire was left unexamined in the media coverage.

The discussion of the coverage of Pew report revealed several points. First, the timing, three weeks ahead of crucial assembly elections, did not receive much attention except in passing in an article in Firstpost. This year, the Spring survey report was published in mid-November compared to mid-September in the last two years.

Before the release of the complete report, Pew had already used its Indian survey results in its multi-country thematic reports, whose release did not attract much attention in the media. So, information/statistics do not freely flow into our public spaces. We choose what is allowed in and when. And, as pointed out next, we also choose how to represent statistical “facts.”

Second, while the Pew data can only support historical statements, most news items and articles carried headings that anachronistically converted historical data (Feb-Mar 2017) into sources of information about the present. This is reminiscent of the use of adjectives in the partisan commentary on the first anniversary of demonetisation.

The interface between language and statistics and prose renditions of statistics needs to be followed with greater care in the future, particularly, in the run-up to the 2019 elections.

Third, hardly any news item tried to provide comparable statistics from other sources to allow readers some means of cross-examining claims. This points to the limitation of our news media vis-à-vis the new language (statistics) that they cannot avoid, but are yet to master.

Last but not the least, the interest in the latest Pew report can be viewed as part of the continued, and mostly unreciprocated, fascination of India and, more generally, of the developing world, with western assessments of their societies.

The ruling party obviously welcomed the results of a “detailed” survey conducted by a "well reputed and credible" think-tank based in the US, but not long ago it was upset with the international press and credit rating agencies for misrepresenting India.

Vikas Kumar teaches economics at Azim Premji University.