Use of social media for news falling, says Reuters report

Overview and Key Findings of the 2018 Report

This year’s report contains signs of hope for the news industry following the green shoots that emerged 12 months ago. Change is in the air with many media companies shifting models towards higher quality content and more emphasis on reader payment. We find that the move to distributed content via social media and aggregators has been halted — or is even starting to reverse, while subscriptions are increasing in a number of countries. Meanwhile notions of trust and quality are being incorporated into the algorithms of some tech platforms — as they respond to political and consumer demands to fix the reliability of information in their systems.

And yet these changes are fragile, unevenly distributed, and come on top of many years of digital disruption, which has undermined confidence of both publishers and consumers. Our data show that consumer trust in news remains worryingly low in most countries, often linked to high levels of media polarisation, and the perception of undue political influence. Adding to the mix are high levels of concern about so-called ‘fake news’, partly stoked by politicians, who in some countries are already using this as an opportunity to clamp down on media freedom. On the business side, pain has intensified for many traditional media companies in the last year with any rise in reader revenue often offset by continuing falls in print and digital advertising. Part of the digital-born news sector is being hit by Facebook’s decision to downgrade news and the continuing hold platforms have over online advertising.

With data covering nearly 40 countries and five continents, this research is a reminder that the digital revolution is full of contradictions and exceptions. Countries started in different places, and the speed and extent of digital disruption partly depends on history, geography, politics, and regulation. These differences are captured in individual country pages that can be found towards the end of this report. They contain important industry context written by local experts — alongside key charts and data points from each market. The overall story is captured in this executive summary, followed by chapters containing additional analysis on key themes.

Summary of some of the most important findings

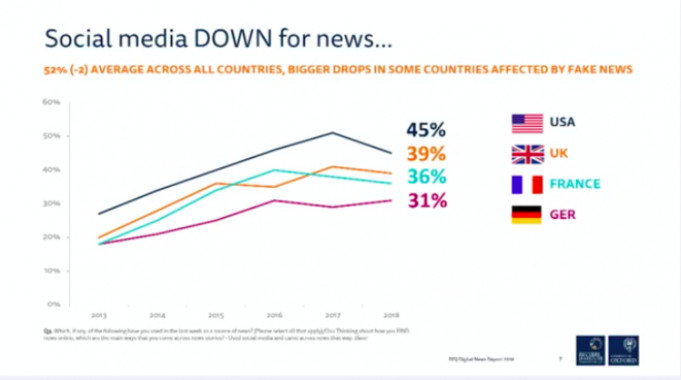

- The use of social media for news has started to fall in a number of key markets — after years of continuous growth. Usage is down six percentage points in the United States, and is also down in the UK and France.1 Almost all of this is due to a specific decline in the discovery, posting, and sharing of news in Facebook.

- At the same time, we continue to see a rise in the use of messaging apps for news as consumers look for more private (and less confrontational) spaces to communicate. WhatsApp is now used for news by around half of our sample of online users in Malaysia (54%) and Brazil (48%) and by around third in Spain (36%) and Turkey (30%).

- Across all countries, the average level of trust in the news in general remains relatively stable at 44%, with just over half (51%) agreeing that they trust the news media they themselves use most of the time. By contrast, 34% of respondents say they trust news they find via search and fewer than a quarter (23%) say they trust the news they find in social media.

- Over half (54%) agree or strongly agree that they are concerned about what is real and fake on the internet. This is highest in countries like Brazil (85%), Spain (69%), and the United States (64%) where polarised political situations combine with high social media use. It is lowest in Germany (37%) and the Netherlands (30%) where recent elections were largely untroubled by concerns over fake content.

- Most respondents believe that publishers (75%) and platforms (71%) have the biggest responsibility to fix problems of fake and unreliable news. This is because much of the news they complain about relates to biased or inaccurate news from the mainstream media rather than news that is completely made up or distributed by foreign powers.

- There is some public appetite for government intervention to stop fake news, especially in Europe (60%) and Asia (63%). By contrast, only four in ten Americans (41%) thought that government should do more.

- For the first time we have measured news literacy. Those with higher levels of news literacy tend to prefer newspapers brands over TV, and use social media for news very differently from the wider population. They are also more cautious about interventions by governments to deal with misinformation.

- With Facebook looking to incorporate survey-driven brand trust scores into its algorithms, we reveal in this report the most and least trusted brands in 37 countries based on similar methodologies. We find that brands with a broadcasting background and long heritage tend to be trusted most, with popular newspapers and digital-born brands trusted least.

- News apps, email newsletters, and mobile notifications continue to gain in importance. But in some countries users are starting to complain they are being bombarded with too many messages. This appears to be partly because of the growth of alerts from aggregators such as Apple News and Upday.

- The average number of people paying for online news has edged up in many countries, with significant increases coming from Norway (+4 percentage points), Sweden (+6), and Finland (+4). All these countries have a small number of publishers, the majority of whom are relentlessly pursuing a variety of paywall strategies. But in more complex and fragmented markets, there are still many publishers who offer online news for free.

- Last year’s significant increase in subscription in the United States (the so-called Trump Bump) has been maintained, while donations and donation-based memberships are emerging as a significant alternative strategy in Spain, and the UK as well as in the United States. These payments are closely linked with political belief (the left) and come disproportionately from the young.

- Privacy concerns have reignited the growth in ad-blocking software. More than a quarter now block on any device (27%) — but that ranges from 42% in Greece to 13% in South Korea.

- Television remains a critical source of news for many — but declines in annual audience continue to raise new questions about the future role of public broadcasters and their ability to attract the next generation of viewers.

- Consumers remain reluctant to view news video within publisher websites and apps. Over half of consumption happens in third-party environments like Facebook and YouTube. Americans and Europeans would like to see fewer online news videos; Asians tend to want more.

- Podcasts are becoming popular across the world due to better content and easier distribution. They are almost twice as popular in the United States (33%) as they are in the UK (18%). Young people are far more likely to use podcasts than listen to speech radio.

- Voice-activated digital assistants like the Amazon Echo and Google Home continue to grow rapidly, opening new opportunities for news audio. Usage has more than doubled in the United States, Germany, and the UK with around half of those who have such devices using them for news and information.

Social Media Reverse

For the last seven years we have tracked the key sources for news across major countries and have reported a picture of relentless growth in the use of social media for news. Now, in many countries, growth has stopped or gone into reverse.

Taking the United States as an example, weekly social media use for news grew steadily from 27% in 2013 to a peak of 51% before falling back significantly this year to 45% (-6). To some extent this represents a readjustment after the social media frenzy around the Trump inauguration last year — but these patterns also exist elsewhere. In the UK usage grew from 20% in 2013 to 41% in 2017 before falling back. The decline in Brazil appears to have started in 2016.