Green journalists, red zones

A toxic and dangerous climate is how Reporters Without Borders describes the working conditions of journalists who cover the environment. Excerpts:

Devastating Hurricanes

Journalists who cover environmental issues live in a dangerous climate and are exposed to potentially devastating forces. We are not talking about nature’s hurricanes, squalls, downpours or lightning. Overly inquisitive journalists face harassment, threats, physical violence and sometimes even murder.

As representatives from throughout the world prepare to attend the Paris climate talks (COP21), which will be covered by more than 3,000 journalists, Reporters Without Borders (RSF) has investigated threats to freedom of information about the environment rather than threats to the environment itself. The journalists accredited to COP21 will in no danger (except the danger of pressure from lobbyists) but the same cannot be said of many of their colleagues, who are often exposed to terrible dangers.

At the intersection of political, economic, cultural and sometimes criminal interests, the environment is a highly sensitive subject, and those who shed light on pollution or any kind of planetary degradation often get into serious trouble. Since RSF’s previous reports on this subject – The dangers for journalists who expose environmental issues in 2009 and Deforestation and pollution, high-risk subjects in 2010 – the situation of environmental reporters has worsened in many countries.

In Hostile Climate for Environmental Journalists, RSF highlights the need for much more attention to the plight of these men and women, who take great risks to challenge powerful interests. Their meticulous work of gathering and disseminating information is essential to achieving the badly needed increase in awareness of the dangers threatening our planet.

Christophe Deloire

Secretary-General

SIX GREEN JOURNALISTS IN RED ZONES

MIMMO CARRIERI

(Italy), threatened

A reporter for the online newspaper Viv@voce and active environmentalist in Italy’s southern Apulia region, Mimmo Carrieri was insulted and beaten for more than an hour by around 20 campers on 5 July when he photographed them in a nature reserve where access was supposed to be restricted. His camera and mobile phone were taken. Repeatedly threatened by the local mafia, Carrieri has been under police protection since 2012. His boat was sabotaged, his car was set on fire and he has received threatening letters containing bullets. He describes himself as a moving target and has requested better protection.

TAHAR DJEHICHE

(Algeria), prosecuted

Algerian cartoonist Tahar Djehiche is opposed to the use of fracking to extract gas from shale and expresses his opposition in articles and cartoons critical of President Bouteflika and his government. In a cartoon posted on his Facebook page in April 2015, he portrayed Bouteflika inside an hourglass collapsing under the sand of In Salah, where residents have been protesting about shale gas production. On 20 April he was charged with defaming and insulting the president, which carries a possible six-month jail sentence. Fortunately, he was acquitted.

RODNEY SIEH

(Liberia), held for several months

The founder and editor of the investigative newspaper Front page Africa, Rodney Sieh was jailed in August 2013 for refusing to pay the colossal sum of 1.6 million dollars (1.2 million euros) in damages in a libel suit dating back to 2010. The suit was brought by a politician in revenge for a story in the newspaper, with supporting evidence, that he was fired as agriculture minister for embezzling 6 million dollars. As well as the damages award, a supreme court judge sympathetic to the former agriculture minister’s cause also ordered Front page Africa’s closure. While imprisoned, Sieh went on hunger strike and had to be hospitalized. He was then paroled on “compassionate” grounds but was confined to his home. He was finally granted a full release on 8 November 2013. Ten days later, the newspaper resumed publishing. “We are coming back stronger than ever,” Sieh announced.

ANNA GRITSEVITCH

(Russia), arrested

An environmental reporter for the leading news website Kavkasky Uzel, Gritsevich, 38, has paid a great deal of attention to the ecological damage caused by the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics. She was sentenced to three days in prison in July 2015 on a charge of refusing to obey police instructions while filming a demonstration by Sochi residents in protest against the dumping of rubble near a nature reserve outside the city. Her camera was also confiscated.

SANDEEP KOTHARI and JAGENDRA SINGH

(India), murdered

Jagendra Singh died on 8 June from the burn injuries he sustained when police raided his home in the northern state of Uttar Pradesh. A freelancer for Hindi-language newspapers for more than 15 years, he had recently posted an article on Facebook accusing an Uttar Pradesh government minister, Ram Murti Verma, of involvement in illegal mining. A forensic report concluded that he took his own life. The burned body of Sandeep Kothari, 40, a reporter for several Hindi newspapers, was found 12 days later in the neighbouring state of Madhya Pradesh. The police said local organized crime members had pressured him to stop investigating illegal mining. Three arrests were made.

******

WHAT IS WRONG WITH US?

For a long time, nobody paid much attention to the environment and nobody paid much attention to journalists who covered the environment. But this is beginning to change.

“What is wrong with us?” asks Canadian journalist and writer Naomi Klein, referring to our collective failure to react to the urgency of the climate change challenge. “What is really preventing us from putting out the fire that is threatening to burn down our collective house?” Covering environmental issues has never been so important because fossil energy is still responsible for 80 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions and 67 percent of greenhouses gases, because global warming is the 21st century’s biggest public health threat and has already displaced 20 million people and because decision-makers need to agree to limit the global surface temperature rise to 2°C at the Paris conference in December.

“There is no bigger story than the climate,” said Alan Rusbridger, the editor of the British daily The Guardian, in an interview for Le Monde in April 2015. Before standing down as editor in the summer, he persuaded his staff to take up the fight against climate change. The newspaper is addressing this “this huge, overshadowing, overwhelming issue” by means of its “Keep it in the ground” campaign – by publishing reports on the causes of global warming and by urging investors, banks, foundations and universities not to put their money in the 200 companies that are the leading producers of fossil energy.

******

A POLITICAL AND ECONOMIC ISSUE

The sudden awakening to the overriding importance of this issue has spread to many other news organizations. The stereotypes about environmental journalists are being exploded. No, they don’t just go on about protecting nature, fauna and flora. They also cover deforestation, the exploitation of natural resources and pollution – issues that often involve more than just protection of the environment, especially when they shed light on the illegal activities of industrial groups, local organized crime and even government officials.

Global warming is a “political and economic issue,” Rusbridger said in the Le Monde interview. Environmental stories used to be discussed last in editorial conferences but now they jostle with the big news stories for the front page or for the start of TV news programmes. It’s also time to assign the same priority to protecting environmental reporters.

******

INDIA AND CAMBODIA – DEADLIEST COUNTRIES

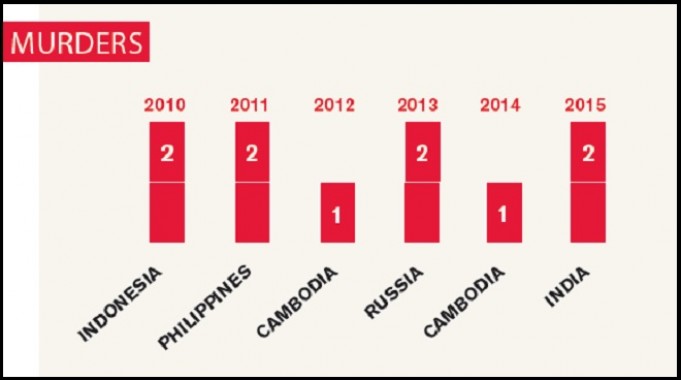

Many environmental journalists have paid a high price. Ten have been murdered since 2010, according to RSF’s tally.

In the past five years, almost all (90 percent) of the murders of environmental journalists have been in South Asia (India) and Southeast Asia (Cambodia, Philippines and Indonesia.) The one exception is Russia. Mikhail Beketov, the editor of Khimkinskaya Pravda, a local paper based in the Moscow suburb of Khimki. He finally succumbed in April 2013 to the injuries he sustained in November 2008, when he was beaten and left for dead while campaigning against the construction of a motorway through Khimki forest. After the beating, he remained badly handicapped until his death.

The two murders of environmental journalists reported in 2015 have been in India. Jagendra Singh, in Uttar Pradesh, as mentioned earlier, had often accused Ram Murti Verma, a minister in the state’s government, of corruption in connection with illegal mining and land seizures. He was never able to produce evidence because he sustained very bad burn injuries during a police raid on his home on 1 June and died eight days later in hospital. Before dying, he accused Verma in a video. “Why did they have to burn me?” he asked. “If the minister and his people had something against me, they could have hit me and beaten me, instead of pouring kerosene over me and burning me.” He was 42.

Sandeep Kothari in Madhya Pradesh, also covering illegal mining and quarrying and had just filed a complaint against the “sand and manganese” mafia when he was murdered on 19 June. He and a friend were riding a bicycle when they were rammed by a car from which several individuals emerged and abducted the reporter. His burned body was found in a farm a few kilometres away the next day. The police noted that he had been the target of judicial harassment by organized crime members. They had also “threatened” his family, they said. He was 40.

Covering such subjects in India or nearby countries is “always risky,” especially for those working living in small towns and villages, says Joydeep Gupta, an Indian journalist who has specialized in covering the environment since the Bhopal disaster in 1984.

******

CAMBODIA

A total of four environmental reporters were killed in Cambodia from 2012 to 2014. Two of them were killed while investigating illegal logging, a lucrative activity controlled by persons in high places. Taing Try was shot dead in his car in the southern province of Kratie on 12 October 2014. The police detained three persons suspected of killing him because he had threatened to report their trafficking to the authorities. The body of Vorakchun Khmer reporter Hang Serei Oudom was found in the trunk of his car in the northeastern province of Ratanakiri on 9 September 2012. He appeared to have been killed by blows with an axe. His last story accused an army officer of using military vehicles for trafficking in timber.

Fishermen beat local newspaper reporter Suon Chan to death with stones and bamboo sticks outside his home in the central province of Kampong Chhnang on 1 February 2014 because his coverage of illegal fishing had prodded the police into taking measures against some of them.

Chut Wutty, an environmentalist who worked as a fixer, was killed on 26 April 2012 in the southwestern province of Koh Kong while accompanying two Cambodia Daily journalists who were doing a story on wine production in a protected forest region. On their way back, they were stopped at a checkpoint where military police asked them for the memory cards of their cameras. ChutWutty refused and, when he started the car with the aim of leaving, the police shot him.

Cambodian journalist Taing Try, 40, was killed in the southern province of Kratie on 12 October 2014.

******

CORRUPTING THE MEDIA

Like political and business reporters, some environmental reporters acknowledge that they have been approached by companies trying to protect their image. To avoid being associated with an environmentally harmful project, these companies have tried to buy their silence.

“To a greater or lesser degree, we regularly receive pressure over which stories we cover and how we cover them,” says James Randerson, the editor of The Guardian’s “Keep it in the ground” campaign. The attempts to manipulate and even bribe usually come from the private sector, from big and small companies. RSF has identified several kinds of pressure, all more or less insidious.

Canadian journalist Stephen Leahy recalls being the target of a bribery attempt in 2008 while investigating a Canadian company accused of polluting the water where it was mining for silver in Mexico. “In a phone interview I asked an executive of the company about the allegations and he immediately said something like, ‘How much is this going to cost me to make this story turn out right?’

In Canada, even the police have tried to bribe the media. In 2013, Mike Howe, a reporter for the Media Co-Op news website, was arrested three times during anti- fracking protests in New Brunswick without initially being charged. “The funny thing about this situation is that one week ago they were offering me money to inform for them and now they are charging me with an incident that allegedly occurred two weeks ago,” he told the press after he was finally charged.

Corruption methods are more direct in Democratic Republic of Congo. In the east of the country, there is opposition to British oil company Soco International’s concession to explore for oil in Virunga National Park, a region with more biodiversity than anywhere else in Africa. A Radio Omara journalist in Kyondo, a town near the exploration area, told RSF: “A Soco agent came to our radio station and gave us 100 dollars [90 euros] to broadcast an audio clip singing the company’s praises. And then he gave us another 50 dollars so that we wouldn’t talk negatively about Soco.”

There has been a great deal of controversy about Soco’s practices in connection with this project. Global Witness, an NGO that campaigns against destruction of natural resources, accused Soco in June 2015 of paying tens of thousands of dollars to a Congolese army officer implicated in a series of violent incidents against the opponents of oil exploration in Virunga. The company denies all these charges and says it has pulled out of the park after completing the exploration phase.

“Our job is to report accurately and stand firm in the face of such pressure,” Randerson says.

*****

WORKING TOGETHER

RSF notes the increasing strength of environmental journalists’ associations opposing governmental and corporate attempts to restrict freedom of information.The first organization of this kind was formed by a small group of established environmental reporters in the United States in 1990. Among its goals, the Society of Environmental Journalists (SEJ) includes the provision of “vital support to journalists of all media who face the challenging responsibility of covering complex environmental issues.” Many other journalists have taken note. Today the SEJ is one of the biggest associations of its kind and similar groups have been formed in around 20 other countries.

James Fahn set up the Earth Journalism Network, an international network of environmental journalists, in 2004 with the aim of helping to create and fund local organizations, especially in Southeast Asian countries such as the Philippines. “Thanks to these grants, they can hold training workshops or carry out other activities to build capacity or produce content,” he says.

In the course of ten years, EJN has acquired 8,000 members in associations throughout Southeast Asia and has trained more than 4,300 journalists, who wrote around 5,000 environmental stories at the end of their training before going back to their regular jobs. Not a bad way to help preserve freedom of information.

The full report is available here: “Hostile climate for environmental journalists”