RTI: Triumphs and Infirmities

It is difficult to overstate what the 2005 Right to Information Act has come to mean for Indian democracy. Civil servant and diplomat Gopal Gandhi, on the 10th anniversary of the Act, has put it up there, alongside the Constitution and the People’s Representation Act, as a tool of empowerment for citizens demanding answers from the government of the day. The RTI is a transparency mechanism that countries around the world are increasingly adopting. In 2014, Paraguay became the 100th country to have a freedom of information law.

And yet, in practice, the RTI in India can be stymied by the bureaucracy. Here we look at its achievements so far and its drawbacks, the dilutions that have accreted, the weaknesses in both the law and its implementation, and the triumphs of RTI activists.

TRIUMPHS OF RTI

The RTI has been used, among other things, to expose human rights violations and corruption, improve entrance exam procedures, usher in more transparency in the judiciary, and provide information about government schemes:

1. Making MNREGA more accountable

2. Human rights

As lawyer Vrinda Grover put it in the Tehelka cover story on RTI, the law has helped expose state violence. The first example was the Hashimpura massacre in Uttar Pradesh in 1987 in which 40 Muslim men were abducted and killed. Two survivors and 36 relatives of the victims filed 615 RTI applications. Grover says that though the inquiry report was not made public, confidential reports of each of the 19 accused policemen were obtained. These showed that none of them was suspended beyond a year and not one of the reports even mentioned the mass murder charges against them. The RTI, a law which came into effect 18 years after the atrocity, was used to pursue justice.

A second example is an RTI that Grover filed in her own name with the Ministry of Defence in 2011 about human rights violations in Kashmir. She wanted to know how many applications seeking permission for prosecution had been received by the Ministry from 1990-2011. “The response said that 44 applications for prosecution were received, out of which 33 were rejected and 11 were pending, which means they had not granted a single permission to prosecute any member of the army. This information, received through RTI, exposed the ministries and armed forces who claim that they had zero tolerance for human rights violations,’ said Grover.

3. Entrance exam reform

The Times of India reported in October 2011 that the Supreme Court praised Rajeev Kumar, a professor of computer science, IIT Kharagpur, for using the RTI to improve the cutoff procedures for admission into IIT. "In fact, the action taken by the appellants in challenging the procedure for JEE 2006, their attempts to bring in transparency in the procedure by various RTI applications, and the debate generated by the several views of experts during the course of the writ proceedings, have helped in making the merit ranking process more transparent and accurate,’ said the judges.

They added: "IITs and the JEE candidates who now participate in the examinations must, to a certain extent, thank the appellants for their effort in bringing such transparency and accuracy in the ranking procedure."

4. Scams uncovered through RTI

Several gigantic scandals would not have come to light without the RTI:

The Adarsh housing scam:The Adarsh housing scam in Bombay was exposed after RTI activist Simpreet Singh filed RTI applications on behalf of the National Alliance for Peoples Movement to investigate Adarsh, the tower block meant for Kargil war widows but usurped by state bureaucrats, politicians and defence personnel who had no role in Kargil. Seven RTI queries were filed asking for details of file note and sale of land and environmental clearances, with the Mumbai collectorate, state revenue department, Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority, and other departments.

The RTI replies showed a range of irregularities including the fact that the building had no environmental clearance and that the then state urban development secretary P. V. Deshmukh used a communication from the Ministry of Environment and Forests to show that Adarsh had environmental clearance. The file note also showed in chronological order how each minister and bureaucrat who got a flat in Adarsh was involved at some point or other in granting permits such as the commencement and occupation certificates. The final list of 103 members showed that hardly any Kargil widows were given flats.

The 2G scam:The RTI filed by activist Subhash Chandra Agarwal on the 2G scam was first denied. The CPIO of the Department of Telecom (DoT) refused to answer the queries posed in the RTI, prompting Agarwal to appeal before the Central Information Commission. It was only after the Commission struck off the grounds that had been cited by DoT for denying information that Agarwal was able to get the information from the office of the Attorney General.

Commonwealth Games scandal:It was Agrawal again, along with others, who helped uncover many aspects of the Commonwealth Games scam. The answers to their RTI petitions exposed the inflated construction cost of the Commonwealth Games projects which had gone up multifold from the time the Games were first conceived.

More transparency in the judiciary

Agrawal was also the RTI activist responsible for all judges declaring their assets before the Chief Justice of India. Initially, the Supreme Court Registry resisted sharing any information with Agrawal, who wanted to know how many judges were complying with the rule requiring judges to declare their assets. The Central Information Commission rejected the stand taken by the Registry and ordered the information to be revealed. The Registry challenged this ruling in the courts but the Delhi High Court upheld the Commission’s ruling and asked the Supreme Court to provide the information within four weeks.

RTI INFIRMITIES

The RAAG RTI study on the implementation of the RTI regime in India carried out surveys in 10 states and found some major weaknesses:

- 35,000 cases are pending: The rise in pending cases has led to huge delays. At the current levels of pendency and rate of disposal, an appeal filed today with the West Bengal State Information Commission (SIC) will be taken up for consideration only after 17 years … The paucity of commissioners in some of the commissions and the low productivity of some of them, mainly due to inadequate support, seem to be the main reasons for the delays. Another factor is the lack of a legally prescribed deadline for disposing of applications and appeals.

- Not enough independence for the SICs: Many information commissioners feel that their dependence on the government for budgets, sanctions and staff seriously undermines their independence and inhibits their functioning.

- Narrow composition of SICs: The composition of SICs has a bias towards retired government servants. A more balanced composition would be better so that diverse expertise is represented in the commission.

- Need for monitoring: The mechanisms for monitoring the implementation of the RTI Act - and for receiving and assimilating feedback - are almost non-existent.

- No training: Nearly 45 per cent of the Public Information Officers have not received any training in the RTI Act. In fact, the PIOs interviewed identified lack of training as their number one constraint. A much larger proportion of non-PIO civil servants, who have to provide information to the PIOs or function as first appellate authorities, have also not been oriented and trained towards facilitating the right to information.

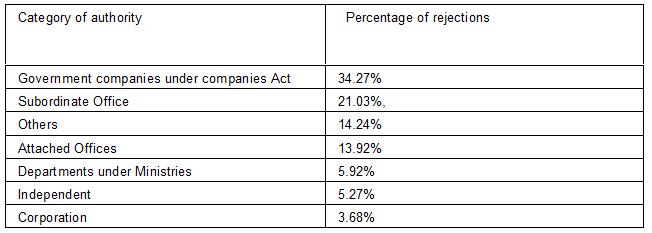

RTI APPLICATION REJECTIONS

According to CICs 2013-2014 report, the rejection percentage of applications during 2013-14 has gone down as compared to the preceding year. However, it is not possible, merely on the basis of the rejection percentage alone, to draw definitive conclusions about the performance of the PIOs while taking decision about the requests for information since only slightly over 72% of the public authorities have submitted their returns for all four quarters in the reporting year.

Percentage of rejection of RTI applications

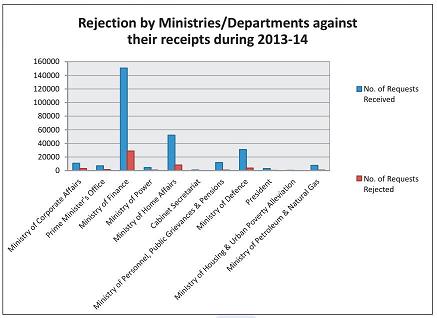

Rejections by the major Ministries/Departments

The Ministry of Corporate Affairs tops the list, followed by the Prime Minister’s Office, and the Ministries of Finance, Power, and Home Affairs.

Proportion of Rejections at the RTI Application Stage

Anecdotal evidence across the country has made many civil society actors and activists believe that rejection of applications is the norm in many public authorities which, they feel, is tantamount to reversing the very purpose of the RTI Act. However, if the data published in the Annual Reports of Information Commissions covered by the CHRI study is to be believed, only a small proportion of the total number of requests is rejected at the application stage. Main findings of the study:

In states with smaller populations like Meghalaya and Mizoram, less than 1% rejection was reported at the RTI application stage.

In Karnataka where public authorities received close to 2.93 lakh requests, the proportion of rejections was a mere 0.30%.

Some of the highest proportions of rejections were observed in the context of public authorities under the Central Government (8.14%) and in Maharashtra (7.2%), both of which received more than 6.5 lakh applications.

Although the macro picture in all governments covered by this study indicates rejection of not more than 10% of the total number of RTI applications, some public authorities had very high rates of rejection. For example, the rejection rate at the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence and the Directorate General of Safeguards was 100%. The offices of the Director General, Income Tax (Investigation) based in Ahmedabad was 86.8%, Jaipur 71.6%, Kolkata 66.7% and New Delhi 59.5%.

The Jammu & Kashmir State Information Commission has reported that while RTI applications received grew phenomenally, the rejection rate dropped from 9% (2009‐10) to 4% (2010‐11) and stood at 1.37% for the last reporting year (2011‐12).

Only the Central Information Commission and the State Information Commissions of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka have provided in their annual reports a clause‐wise break up [Sections 8(1) (a) to (j), 9 and 24] of the number of times the exemptions were invoked by public authorities to reject information requests at the application stage.

The largest number of rejections of RTI applications (15,279) in public authorities under the Central Government were based on the grounds of protecting personal privacy [Central RTI Act, Section 8(1)(j)]. In Andhra Pradesh, the exemptions pertaining to contempt of court and prohibition on the disclosure of information by courts were invoked most frequently (131 times) to reject applications [Central RTI Act, Section 8(1)(b)]. And in Karnataka, the public authorities are said to have invoked the exemption relating to police investigation, arrests and criminal trials [Central RTI Act, Section 8(1)(h)] over 100 times.

More than 4,000 RTI applications are said to have been rejected because they pertained to the 25 intelligence and security organisations notified by the Central Government under Section 24 of the Central RTI Act.

ACCRETIONS THAT HAVE WATERED DOWN RTI

Agencies such as the Central Bureau of Investigation, the Intelligence Bureau, the Research and Analysis Wing, and the Enforcement Directorate are excluded from the purview of the RTI Act. So too is any information that may affect the security and sovereignty of India, that has been withheld by a court or that comes under the privileges of Parliament and State Assemblies.

Apart from this, amendments to the original Act have diluted its impact. Section 8 (1) of the RTI Act excludes access to information which is personal in nature and has no bearing on any public activity or interest, or which would cause an unwarranted invasion of the privacy of the individual unless the Central Public Information Officer or the State Public Information Officer or the appellate authority is satisfied that the larger public interest justifies the disclosure of such information.

Further, Section 2 of the RTI Act as amended in 2013 says that political parties cannot be treated as public authorities: “An authority or body or institution of self-government established or constituted by any law made by Parliament shall not include any association or body of individuals registered or recognised as a political party under the Representation of the People Act, 1951.”

And a new Section 31 in the Act says that this amendment will apply “notwithstanding anything contained in any judgment, decree or order of any court or commission..,” and will prevail over “any other law for the time being in force.”

Dilution on account of Supreme Court judgements

One case which has resulted in a watering down of the RTI Act was that of Girish Deshpande vs CIC where the petitioner sought details of the respondent’s movable and immovable properties and other details of his financial transactions. It was decided that this information featured in the respondent’s income tax returns. The Supreme Court had to consider whether this information qualified as “personal information” as defined in clause (j) of Section 8 (1) of the RTI Act. The Supreme Court held in this case that income tax details can be disclosed only if they are in “the larger public interest”.

According to former CIC Shailesh Gandhi, the judiciary’s approach to transparency has become an impediment to widening the application of the RTI. “In the last five years, it appears that the decisions of various courts are expanding the grounds on which information can be denied. Out of 16 apex court judgments I have analysed, only one gave an order to furnish information ... many judgments are expanding the exemptions in a manner which is not in consonance with the law or the Constitution,” said Gandhi.