Naga media, the elections and ‘solutions’

Assembly elections were held this February in three states of the North East, including Nagaland. It was feared that the elections would be boycotted in Nagaland because of the ‘Solution before Election’ campaign in which civil society appealed to the government to conclude the two decade old peace process before holding elections.

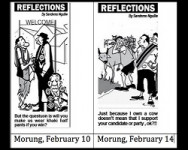

The BJP tried to counter the campaign with its slogan ‘Election for Solution.’ Civil society launched a ‘Core Committee of Nagaland Tribal Hohos and Civil Organisations’ (CCNTHCO) on January 25 to spearhead the campaign.

|

|

Morung, January 23, p. 1 |

Within a week of its launch, the CCNTHCO rallied most insurgent factions and all political parties, including the BJP, in support of the pro-solution campaign and called for a bandh. However, three influential tribal bodies refused to enforce the February 1 bandh in their strongholds covering more than half of Nagaland and on the same day the BJP made public its decision to contest the election.

The CCNTHCO was dissolved on February 6 after all parties announced their candidates and only one “intending” candidate withdrew his candidature. Its failure notwithstanding, civil society’s ‘Solution before Election’ campaign, along with the Church’s ‘Clean Election Campaign’ and the Church’s appeal to the laity to protect the faith, was among the defining features of this year’s election.

The coverage of civil groups’ pre-electoral intervention in Nagaland’s newspapers provides an insight into the changing nature of Naga society. It also exposes a key weakness of these newspapers, namely, the unwillingness to investigate sensitive issues.

The following discussion is based on the coverage of the ‘Solution before Election’ campaign and related events in three English dailies of Nagaland – The Morung Express (henceforth, Morung), Nagaland Post (henceforth, Post), and Eastern Mirror (henceforth, Mirror).

Vox populi

After the pro-solution campaign unraveled, a Morung poll revealed that 62% of respondents believed that tribal and civil society organisations did not represent the “will of the public” (Feb 12) and 79% thought that the legislators should have “resigned by now” if they were serious about “Solution, not Election” (Feb 5).

Some of the respondents, who also submitted comments while voting, saw civil society organisations as unelected bodies controlled by political parties and insurgent groups.

A series of polls in the Post revealed a similar disconnect between civil society and the people. About 92% of respondents believed that the solution to the Naga political problem cannot be achieved within six months (Jan 28) and 84% believed that the solution cannot be reached in 2018 (Feb 17).

So, while 76% of respondents believed that the government was not serious about a solution (Feb 1), 70% felt that the demand for a solution should not be linked with elections (Feb 4).

In other words, the people are tired of waiting for a solution, but they still thought that a ‘Solution before Election’ was unreasonable. While the number of respondents who participated in these polls is not known, the agreement between the outcomes of related polls conducted by Morung and Post is reassuring. Also, noteworthy is the fact that the two leading newspapers of Nagaland, which otherwise differed on the issue of an election boycott, published these polls.

|

|

|

Morung, January 30 |

Morung, February 2 |

|

|

|

Morung, January 29 |

Post, February 6 |

|

|

|

Mirror, January 22 |

Mirror, February 2 |

|

|

|

Mirror, January 30 |

|

For whom does civil society toil?

Several op-ed contributors argued that the pro-solution civil society organisations did not represent the people. The pro-solution campaign was described as “a wag-on of the tail of a dog than... a realistic mass movement of a people” (“Do the NGO & political parties in Nagaland really reflect the mind of the people?” Mirror, Feb 2).

An op-ed written on behalf of “We, the silent public” claimed that “All the news items about civil societies against elections do not express the desire and opinion of the general public… [We] want to have fair and free and clean elections… We are sick and fed up... But we the silent majority are afraid” (We must have elections! Morung, Jan 29).

Morung, whose front page headlines were sympathetic to the pro-solution campaign, agreed that “those who claim to represent the people ignored the “general will” of the people” (“Representation ‘for’ or ‘of’ the People,” Editorial, Feb 7).

Another op-ed reminded civil society groups that people no longer wanted to be dictated to: “While it might be disheartening for those civil societies which had championed the boycott movement, it also explains the changing world we live in where dictation by Tribal Hohos need not necessarily hold sway and individual opinion and space… has become increasingly valued” (“On election, BJP and KK Sema!” Feb 22).

It was also pointed out that the pro-solution campaign overlooked the real problems facing the people such as corruption (Arise for change, Post, 22 Jan). ‘Solution’ was described as the Naga “El Dorado” (The Letters of the Alphabet in Nagaland, Morung, Jan 29).

Yet others complained that the pro-solution campaign created more problems than it hoped to solve. It was held responsible for pre-poll violence in so far as it curtailed normal campaigning to just three weeks, leaving the candidates with no time to rationally persuade voters (“What did you expect?” Post, Feb 13).It was also blamed for derailing the Clean Election Campaign(Test of self-trust, Editorial, Feb 24).

More importantly, it was argued that not only was civil society not interested in the immediate problems facing the people, it had also not done its homework for the pro-solution campaign. It failed to clarify what constitutes an acceptable solution and was trying to rush the peace process, overlooking the difficulty of engaging the second largest insurgent group in the peace process.

A Morung editorial summed up the concern: “In all probability, Nagas are not against a ‘solution’ and nor is it a question of preferring ‘election’ over ‘solution’ but it is a question of what is the ‘solution’ and the process involved that is contentious” (“Interesting times ahead,” Jan 31).

It noted that the “silent majority” was “fed-up of this bandh culture.” It added that “in the current context, also reflecting on the bandh imposed during the proposed ULB elections… negative repercussions may outweigh the positives, if at all” and asked, “Is there no other means than bandh?”

Readers’ polls and critical op-ed contributions raised a question not explored by the newspapers: If so many people believe that tribal organisations and civil society groups do not enjoy popular support and overlook the problems facing the common man, whose interests are served by according importance to these organisations that insist that their consent is essential for practically everything in Nagaland including conducting elections?

Storms in a tea cup?

A few op-ed contributors pointed out that lofty slogans and campaigns were just a façade for the power struggle within civil society. Others lampooned the ever changing arrangements within the various organizations.

“The proponents of the cry for, “Solution before Election” and, “Solution not Election” are in danger of fast using up the letters of the English Alphabet, in all its various permutations and combinations...” (The Letters of the Alphabet in Nagaland, Morung, Jan 29). Both the Post (Money chasers, Feb 20) and Morung (‘Politicised’ Trajectories, Jan 24) agreed that vested interests use the “the Naga political issue”as “a “perfect alibi” either for ‘political leverage’ or ‘gaining mileage.’”

Very few appreciated the fact that the CCNTHCO, at least, showed that it is not impossible to bring together Nagaland’s fragmented civil society, insurgency, and political parties. The dramatic rise and fall of the CCNTHCO reminds of the fate of the Joint Coordination Committee and the Nagaland Tribes Action Committee launched during last year’s anti-women’s reservation protests, only to be forgotten in a matter of a few weeks.

In light of this newspapers should have asked a question: What explains the periodic meteoric rise and fall of civil society conglomerates in Nagaland in recent years? Only two op-eds commented on this.

One of them suggested that ad hoc civil society conglomerates are floated to deal with problems because of the decline of the Naga Hoho, the hitherto dominant pan-Naga civil society organisation (“Revamping the Naga House,” Feb 6).

The other suggested that the ad hoc conglomerates fall apart because they cannot make their constituents implement joint resolutions (“What is the solution, what is the problem?” Feb 1).

The identity of particular tribes and civil society organizations responsible for the breakdown of consensus was noted in newspapers but not examined, i.e., the motives behind their decision to violate joint resolutions were left unexplained.

Since these issues are brushed under the carpet, Nagaland is condemned to suffer periodic upheavals that create more problems than they solve. The lynching incident rocked the state in 2015. Two years later the state relived the horrors during the anti-women’s reservation protests.

This year the state barely escaped a violent showdown on the scheduling of elections. The intense turf wars between old and new groups formed over the past five years and within new generation groups explain most of these upheavals.

Contradictory headlines?

The choice of front page headlines is where the newspapers diverge sharply despite the broad agreement noted above. Morung’s front page headlines suggested that the “Solution before Election” campaign enjoyed widespread support, while the Post and Mirror suggested the contrary.

On January 19, the sub-heading of the main news item on the front page of Morung pointed out that “ECI announcement [was] made despite calls for ‘Solution before Election’.” Post noted the displeasure of the Nagaland-based insurgent factions at the announcement, but also highlighted the government interlocutor’s assurance that the peace process will resume after elections (“Ravi expects talks to resume after election”). Mirror’s front page did not refer to the opposition to elections.

On January 28, Morung suggested broad political support for ‘Solution before Election’ (“Parties seek solution to Naga issue before Assembly polls”). The Post (“Lobby for deferment of Assembly Polls: Pol parties want guarantee for not filing nominations”) and Mirror (“Civil orgs. meet with NPF, NPP and AAP; BJP skips meeting again”) suggested that the parties were divided and those ostensibly supporting the pro-solution campaign were jittery that the BJP might go ahead and file nominations.

On February 1, Morung (“Bandhs in Dimapur, Mokokchung, Peren, Tseminyu and Zunheboto”) simply identified the districts covered by the bandh. On the other hand, the Post (“CCNTCHO to go ahead with bandh; some tribal groups refrain”) and Mirror (“Will-not and the for: Tribal apexes decide state-wide strike”) made it clear that the civil society was divided.

The Mirror’s sub-heading identified the tribal bodies opposed to the bandh. The Post also carried an item “1st death anniversary of Jan 31 martyrs observed”on the front page to possibly remind readers of those who sacrificed their lives in the 2017 anti-women’s reservation protests.

The divergence between the newspapers was perhaps widest on February 2. Morung (“Feb 1 bandh call passes off amidst uncertainty”) devoted the first half of the front page to the bandh, but its headline did not identify the lack of consensus.

The Post (“CCNTHCO bandh evokes mixed response”) and Mirror (“Bandh farce: CCNTHCO maintains brave front”) placed the news at the bottom of the front page and made clear that the bandh had failed. They gave prominence to poll preparations of parties, while Morung placed this news at the bottom.

It is difficult to reconcile the broad agreement between newspapers in readers’ polls, cartoons, and op-eds with the contradiction between their front pages.

Concluding remarks

Nagaland’s newspapers, which are driven by op-ed contributions, can perhaps do only so much in the absence of a culture of serious public debate. Their unwillingness to investigate “sensitive” issues, though, makes matters worse. They discuss problems in the abstract or present problems as collections of unexamined proper nouns and dates.

In fact, they do not even put together a background note compiling all the names and dates, which would facilitate further debate and help uncover the underlying processes. As a result, the factors that facilitated, for instance, the rapid making and unmaking of civil society conglomerates around anti-women’s reservation (2017) and pro-solution (2018) campaigns will remain a mystery to Nagaland’s newspaper reader.

Likewise the people responsible for the 2015 lynching will forever remain anonymous. The investigative silence helps vested interests to avoid public scrutiny. However, there is growing restlessness among people, some of which was reflected in the op-eds published in the run-up to the election.

They are asking uncomfortable questions and challenging orthodoxies and vested interests that have dominated the state for long. It remains to be seen if and how Nagaland’s newspapers engage with these questions.

Vikas Kumar teaches economics at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.