Role of advertising in the Nagaland polls

The recent assembly elections in Nagaland were perhaps the most bitterly contested in recent memory. (Interestingly, until a few weeks before the day of voting, it was not even certain if they would be held). The highlights of the election include the weakening of the decade-and-a-half long dominance of the Naga People's Front (NPF) in Nagaland’s politics; the emergence of another state-level political party, the Nationalist Democratic Progressive Party (NDPP), and the consequent expansion of the space for regional politics in Nagaland; the Nagaland Baptist Church Council’s (NBCC) appeal to people and politicians to protect their faith; the re-emergence of the BJP as the kingmaker in Nagaland after a decade-and-a-half; and the decimation of the Congress.

The BJP’s success can be attributed to a timely alliance, careful choice of candidates including defectors from other parties, and low key micro-level campaigning far ahead of the elections, among other things.

A focused newspaper advertisement campaign also seems to have played a role in its success. However, the nature of the advertisement campaign also raises questions because it seems parties with deeper pockets can block competitors from prime advertisement spaces.

This article examines the larger body of election-related advertisements that appeared in The Morung Express (henceforth, Morung) and Nagaland Post (henceforth, Post), the two leading newspapers of Nagaland, between January 19 (the day after announcement of elections) and February 27 (the day of voting).

The Election Commission released several advertisements that educated voters on the functioning of voting machines and the importance of free and fair elections. We will omit these advertisements in the subsequent discussion and focus instead on advertisements of the parties announcing their policies, rallies, etc and advertisements released by individuals announcing their candidature.

Other advertisements of interest to us, which mostly appeared in the Post, were released by party workers, including dissidents expressing their political preferences, individuals or organisations thanking candidates for favours, and civil society announcing electoral interventions.

Political parties: a last minute dash

Until February 1, when the BJP decided to contest the elections, it was not clear if the elections would be held. Civil society seemed to have successfully coerced all parties into boycotting elections to pressure the government to conclude the two decade old Naga peace process.

The parties declared their candidates just ahead of February 7, the last date for filing nominations. While individuals intending to contest elections and their well-wishers started advertising on January 19, the parties began advertising on February 12, the last date for withdrawing nominations.

There were stray party advertisements before that date, for instance, the National People's Party (NPP) advertised on January 19 (Post and Morung) and January 28 (Post) and the NDPP on January 13 and 15 (Post and Morung).

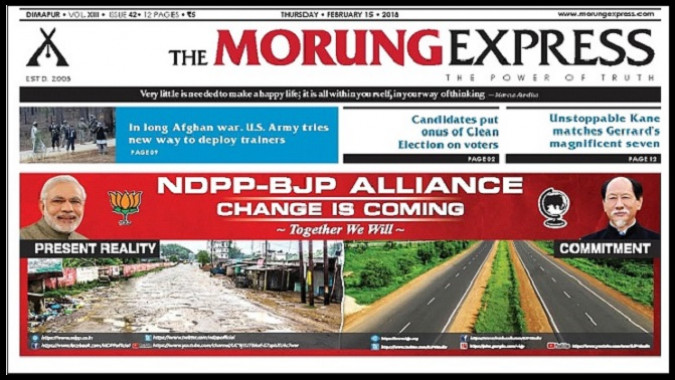

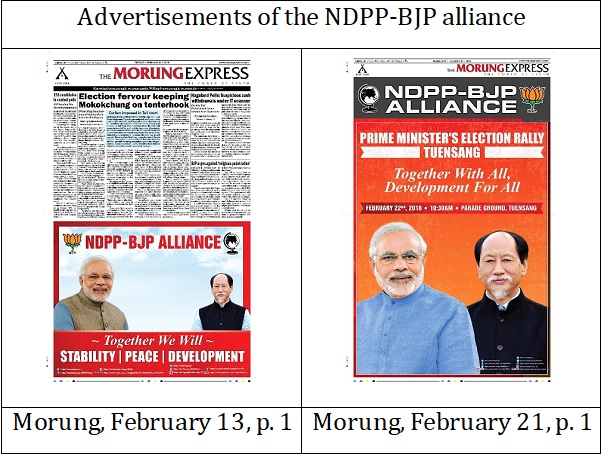

Between February 12 and 25, the NDPP-BJP alliance placed 14 colourful advertisements in the Post and Morung. These include three full page, 7 half page, and 4 quarter page advertisements on Morung’s front page. The Post carried three full page (on Page 2) and eleven half page (on the front page) advertisements.

The alliance also placed two full page advertisements in the Post on February 26 (Highlights of Prime Minister’s Speech at Tuensang) and February 27 (Please vote for NDPP-BJP). The NDPP placed a standalone advertisement in the Post on February 21 (p.16). This is perhaps the first time that a newspaper campaign on this scale was tried in Nagaland.

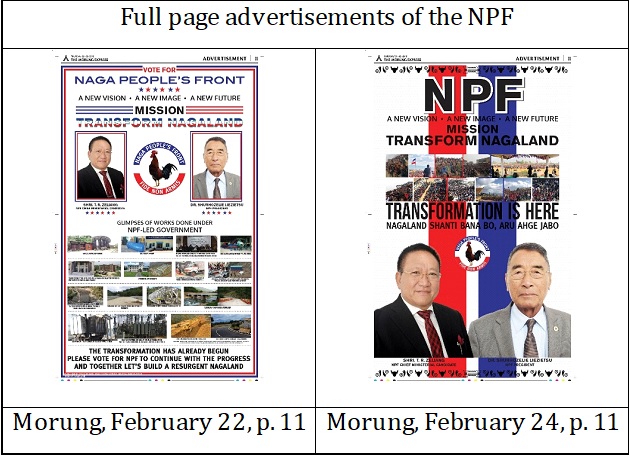

The ruling NPF belatedly responded between February 20 and 25, with six full page coloured advertisements in Morung (Page 11 or 12) and the Post (Page 5 or 7). The NPF also published an appeal to voters on February 25. Other parties such as the Congress did not advertise.

The NPP released a few small advertisements (January 19 and 28, February 16). The Forward Democratic Labour Party released a small advertisement on the occasion of its launch in Nagaland (February 3, p. 9). About five per cent of the candidates, mostly from urban constituencies, placed standalone advertisements. These include two independents, one each from the AAP, the Congress, and the NPP, and two each from the BJP, the NDPP, and the NPF.

Only one of the NPF and both the BJP candidates won their elections. The other NPF candidate, who advertised on several consecutive days, lost the election.

The NDPP-BJP campaign (Change is coming) was designed in a way that aroused curiosity about what would come next in its series of advertisements. The advertisements raised specific issues and made graphic promises about how the alliance intended to address problems.

The NPF’s campaign (Transformation is here) was constrained by anti-incumbency. Moreover, half of the NPF advertisements had a cluttered appearance. About 75% of NDPP advertisements also featured the BJP, its alliance partner. In contrast, only one of the six NPF advertisements made room for its ally the NPP, which joined the NDPP-BJP government after the elections.

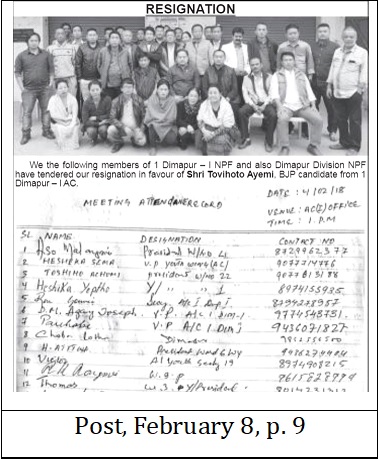

Dissidents sound the trumpet

One or more individuals from one or more parties announcing their resignation to join another party or to support an independent candidate formed the biggest category of advertisements not (directly) sponsored by parties and candidates.

These advertisements differed in terms of whether they were placed by an individual or a group (and if all the names were mentioned or just the names of key figures), were accompanied by a photograph, and indicated both the new and old parties of the signatories.

A small but related category of advertisements involved veteran politicians or notables identifying their preferred candidate. A few advertisements welcomed someone to a party (e.g., “NDPP Kohima Welcomes Neiphiu Rio,” the Post, January 20, p. 9) or thanked the party high command for a favourable decision.

The brisk trade in supporters continued until the very last day of campaigning as reflected in advertisements and it was not always in favour of bigger parties. These advertisements covered more than 16 out of 60 assembly seats.

Their authenticity is suspect, though. For instance, the Post carried a declaration of mass resignations from the Dimapur-III unit of the NPF, including its minority wing (February 4, p. 9). Three days later the NPF’s minority wing clarified that the party did not have constituency-level minority wings. The impact of these advertisements does not seem to be decisive. On six seats the recipients of dissidents won the election, whereas in another six the party hit by dissidence won.

A rare glimpse of the lack of inner party democracy was provided by a “Meeting Declaration” (Post, January 23, p. 4). It conveyed to the party leadership the consensus among party workers in favour of giving ticket to a particular aspirant. In the absence of inner party democracy, loyal party workers had to resort to public fora such as newspapers to voice their concerns. The request was denied and the concerned individual contested from another party and lost the election. It is not clear if his supporters resigned in protest and followed their preferred candidate.

The representation of women and minorities in the advertisements space is a measure of their overall representation in the political system. Only one of the advertisements of the type discussed in this section was placed by a woman, while in the rest the names of women appeared, if at all, below the names of male signatories.

Likewise no one from non-Naga minorities placed any advertisement, though their names figured in a few advertisements placed by Nagas. The absence of women and minorities (excluding the Dimapur-based non-Naga trading communities that avoid the political limelight) in the advertisements is partly explained by their political marginalisation and lack of access to finance.

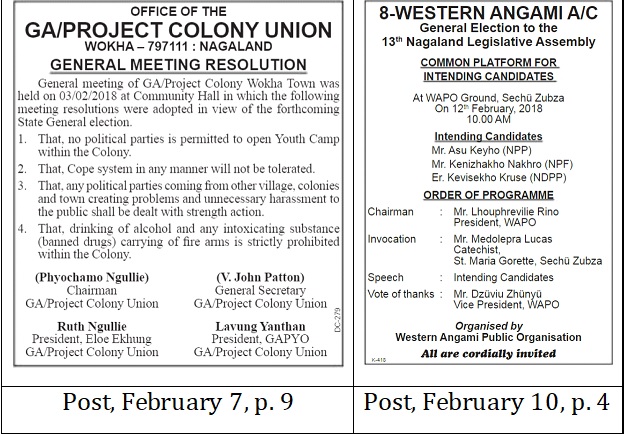

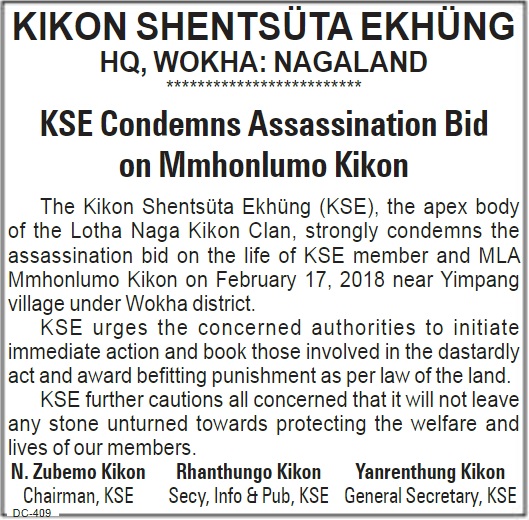

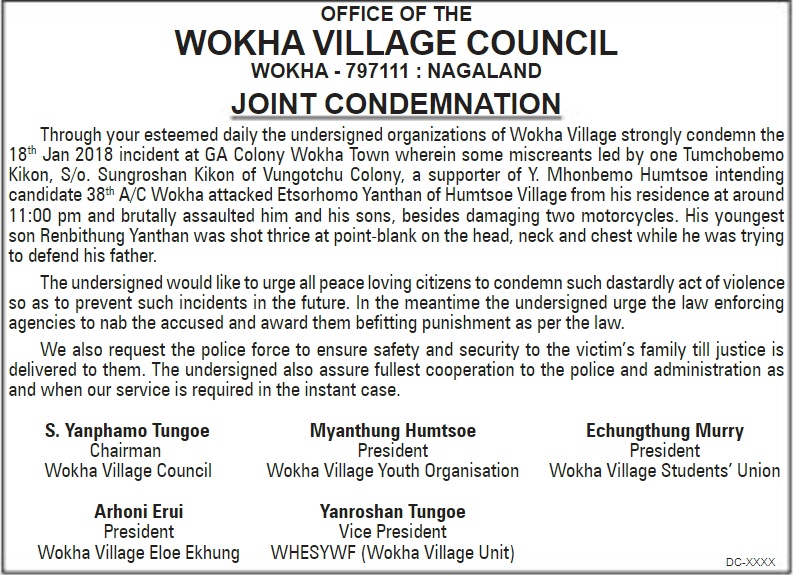

Civil society plays an active role

The second largest category of advertisements not sponsored by parties and candidates includes statements/notices released by village bodies, tribal bodies, colony unions, etc condemning poll-related violence, outlining codes of conduct for campaigners or announcing the schedules of common platforms for candidates.

In the 2013 elections, several village and tribal bodies publicly identified their preferred candidates through ‘Declarations of support’ in newspapers. This time there was no such advertisement, even though these bodies did have favourites as reflected in restrictions on the entry of rivals into villages and poll-related violence targeting supporters ofnon-consensual candidates.

It is possible that en masse resignations involved people from a particular village or clan, but that is difficult to ascertain in the absence of explicit self-identification by the signatories. Even if a background check reveals that all or most signatories belonged to one village or clan, it is interesting that this time they refrained from identifying themselves as such.

This public shift could possibly be read as a major success of the Clean Election Campaign of the Church and other organisations, which was widely criticised for being ineffectual by editorials, op-eds, cartoons, and readers’ polls.

Most of the codes of conduct released by colony unions and village bodies warned parties against running youth camps, organising picnics, intrusive campaigning, putting up posters and banners around churches, shouting slogans or using loud speakers, holding unauthorised public meetings, using the name of the village or colony for partisan purposes, resorting to violence, distributing money, and distributing intoxicants.

A few advertisements also announced common platforms for candidates. Some of these concerns also figured prominently in newspaper cartoons published during the election.

All these advertisements were placed by colony unions and village bodies of just two districts, Wokha and Dimapur, except a notice for common platform in Kohima. Many of them endorsed the Clean Election Campaign of the Church. These advertisements include one each by a group of villages and a non-Naga tribal village. The rest were placed by individual Naga villages or colonies.

All but two advertisements from Wokha were in the Lotha language. Wokha along with Mokokchung was among the districts most affected by poll violence. The first few advertisements from Wokha appeared in January soon after the announcement of the election possibly in anticipation of a pre-poll violence.(The villages of Mokokchung might have placed advertisements in Ao language newspapers.) Most condemnations of poll violence also came from Wokha.

|

|

Post, February 20, p. 9 |

|

|

Post, January 23, p. 9 |

So, while village councils, the traditional civil society in villages, and colony unions, its modern counterpart in towns, did not support specific candidates this time, they nevertheless used the Clean Election Campaign and Common Platforms to reinforce their boundaries and assert their primacy over political parties.

They introduced themselves as interlocutors for political parties trying to approach voters and as a guarantor of peace to common people fearing poll violence and corrosive campaigning. This exemplifies how traditional bodies try to find newer tasks for themselves rather than simply fade away when their older functions become obsolete.

Bouquets and brickbats

Another major category of advertisements includes expressions of gratitude under the title ‘Appreciation,’ ‘Word of gratitude,’ or ‘Acknowledgement’ by sports, students, etc associations and local bodies that thanked candidates who contributed to their annual event, study/cultural tour outside Nagaland, and the renovation of office buildings.

|

|

Post, January 19, p. 9 |

|

|

Post, January 24, p. 9 |

In one case, a family thanked candidates for helping them rebuild their house after a fire. In another, a government department thanked a candidate for reviewing its performance. This candidate won unopposed.

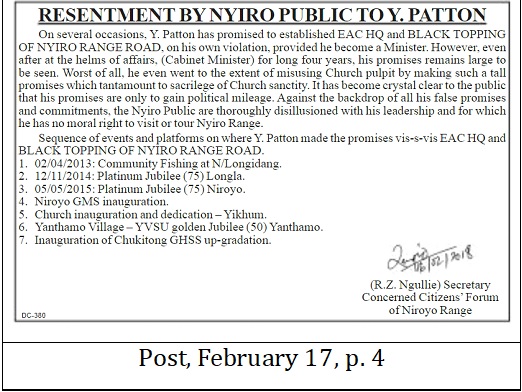

In a rare instance, a Concerned Citizen’s Forum advertised people’s “resentment” against a candidate for not fulfilling past promises about “black topping” of a road and the establishment of a new administrative headquarter. The Forum listed various occasions when commitments were made. The concerned candidate won the election.

People seem to try to hold candidates accountable through advertisements ahead of elections, while candidates try to make visible their patronage networks. The advertisements also reflect the transactional nature of democracy on the ground. By publishing such advertisements the newspapers help to expose at least some of the attempts to buy influence.

Concluding remarks

There were perhaps two major shifts in election-related advertising in Nagaland during the latest elections. Unlike past elections, village and clan bodies did not issue declarations of support in favour of their preferred candidates. In practice, these bodies did try to enforce their choice on their members, but at least they felt shy of going public in newspapers. This positive development could be attributed to the Church’s Clean Election Campaign.

The other shift was towards massive newspaper advertisement campaigning. It is true that manifestos, debates on common platforms, and advertisements do not drive elections in Nagaland, where traditional bodies continue to exercise considerable influence and money, and muscle power plays a major role.

However, growing urbanisation and literacy as well as the reach of news and social media have meant that people can also be mobilised through non-traditional means.

The massive support base built by the Against Corruption and Unabated Taxation through newspapers and social media is a point in case. The movement was derailed during this year’s ‘Solution before Election’ campaign and is unlikely to recover, but its historic contribution to making room for free speech and building awareness about corruption in Nagaland is perhaps second to none.

Also, noteworthy is how in a matter of a few days newspapers and social media mobilised Dimapur against illegal immigrants in the run-up to the lynching of a young man. In short, the power of the media can no longer be ignored.

Closer to our concerns, in this election, the advertisement spending of parties seems to have been correlated with their performance. The NDPP-BJP alliance (30 seats) spent the most on newspaper advertisements, followed by the NPF (26 seats). Together they won 56 of the 60 seats. The NPP, which was a distant third in terms of spending, won two seats.The remaining seats went to a JD(U) candidate, who managed his own campaign, and an independent candidate.

The advertisement campaign of the NDPP-BJP alliance raises questions that have wider relevance for the functioning of electoral democracy. First, the NDPP-BJP alliance seems to have booked front page space in advance, effectively confining the NPF to other pages.

Should newspapers allow one party or alliance to monopolise prime advertisement slots? Is it realistic to expect newspapers to set aside financial considerations to create a level playing field? (Morung, for instance, made an attempt in this direction in a different way, though, by inviting leaders of all parties to an open debate.) Can the Press Council of India provide guidelines in this regard? Should the state step in to level the playing field?

Second, the BJP-NDPP alliance placed advertisements in the Post even on February 26 and 27. The NPF complained against the February 26 advertisement arguing that the NDPP-BJP alliance “violated the Model Code of Conduct by way of making a slew of promises.”

This advertisement does not seem to have violated norms as it listed the “Highlights of Prime Minister’s Speech at Tuensang.” It is not “offending and misleading in nature” and does not make any point that would require another party to necessarily respond. So, the relevant screening committee of the Election Commission would have approved the advertisement.

However, we can still ask if there should be restrictions on advertising after the formal end of campaigning, i.e., “48 hours before polling closes.”Should parties be allowed to cleverly draft their advertisements to mechanically conform to the code of conduct? This issue has also been raised by the Election Commission in the past.

Given all these factors, a debate is needed within the print media on how it should regulate political advertisements and ensure a level playing field for smaller political parties and independents who cannot afford to compete with national political parties.

Newspapers should perhaps not publish any political advertisement on the front page or, at least, not allow any party or coalition to block rivals out of prime advertising spaces and dates. Also, newspapers could, on their own, decide against publishing political advertisements after the end of campaigning.

Postscript: After the publication of the article, the author learnt that Nagaland's newspapers had collectively decided in 2016 to "stop publishing any advertisements and news issued by village councils, or any other non-political organisation that endorses one particular candidate."

Vikas Kumar teaches economics at Azim Premji University, Bengaluru.